|

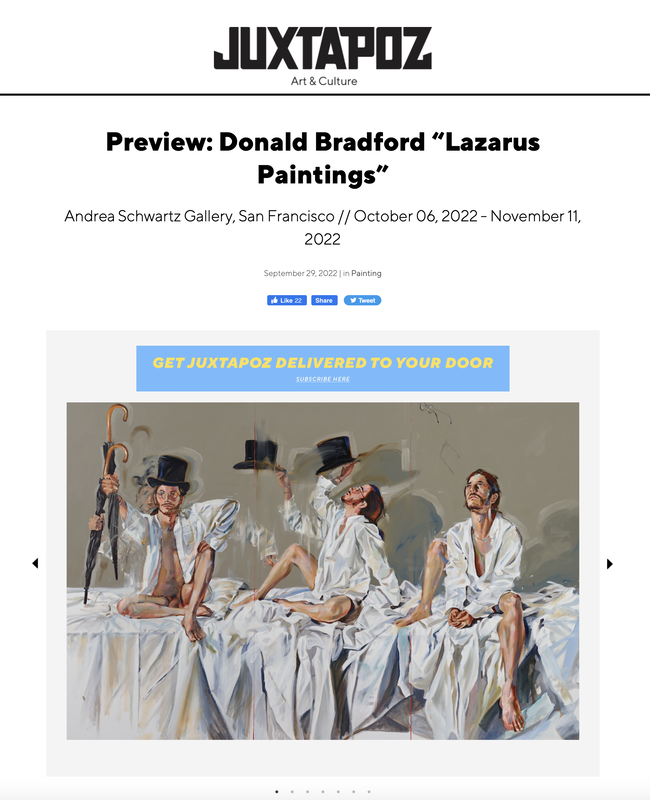

At first blush, the viewer will encounter naked mostly male forms draped, bound, and positioned individually or in a series. Many of the paintings are composed with painted dividing lines reminiscent of the triptych and are titled to evoke classical mythology or biblical parables, such as Lazarus, Icarus, and Jacob wrestling an angel. An intriguing aspect of this body of work is that Braford is returning to motifs and scenes that he first tackled 30 years ago.

Consciously or unconsciously, a painting captures a moment in time in the life of the artist. It’s a snapshot of its maker’s engagement with and reaction to inner experience and exterior conditions. So what is revealed when an artist embraces the “re-recording” of previous explorations? A famous example of this pursuit is the late great pianist Glenn Gould’s benchmark recordings of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, first in 1955 at age 22, and in 1981, a quarter of a century later. The insights offered by Gould’s quite different recordings of the “Goldbergs' ' seem to portray a difference between the frenetic, impatient energy of youth and a slower, more seasoned, self-reflective melancholy. The revelations suggested by Bradford’s variations, however, offer a beguiling twist on the expression of creative evolution. Having seen photographs of Bradford’s earlier portraits of the models and stories now re-recorded in this exhibition, one can certainly note an advance in technical skill and greater narrative depth. Yet, where one might expect a slackening of exuberance and more ruminative, cerebral tone in later portraits, one finds the opposite. Bradford’s is an élan vital on overdrive. The artist is, if anything, doubling down in displaying the visual pleasures offered by the human form and the physical pleasures in the act of painting itself. This is less a backward-looking glance and more a diving into the present with renewed curiosity and gusto. Bradford’s loose, breezy mark-making bespeaks a mature hand that has lost none of its sensual interest but is simply more confident that a deft touch will yield the desired effect. The artist manages to maintain a fine balance between playfulness and serious intent. To create multiple portraits of Lazarus and of Saint Irene in the year 2022, and achieve something fresh and buoyant, is no small feat. These paintings feel modern. They pull you in. They hold you close. A word about bondage might be in order now. What are all these ropes and wraps saying to us? Bradford was a teacher for many years. One of the exercises he used to help students achieve a sense of volume when drawing the human figure or any three-dimensional object, was to have them drap the form in fabric. Is that academic explanation the end of the story? As with any work of art, I’d suggest that the viewer’s own answer may be the most revealing. To this viewer, it appears that there is nothing so illustrative of the physicality of human yearning and the need for individual freedom of expression than a visible tether reining in such elemental, universal forces. Bradford’s Lazarus Paintings resurrect powerful parables and breathe new life into lessons of sacrifice, resilience, and euphoria. The painting Finding Neverland references the film about Sir J.M. Barrie’s friendship with the family that stirred him to write his novel, Peter Pan. The model for Bradford’s painting is his late partner, the artist Richard Bassett. Bradford worked from photos of Bassett garbed in iconic props from the film and taken in the final weeks of his life. Singular paintings of a top hat and umbrella respectively are presented floating above the larger painting, which shows Bassett in a trinity of positions. The shadows behind the hat and umbrella bring to mind the story of Icarus flying towards the sun with wings stretched. The work in this witty and effecting show reminds us that myths serve not only as a compass in navigating daily existence but as a connection point across the arc of human experience and time itself. Text by Tamsin Smith for Juxtapoz

0 Comments

Voyage LA Staff:

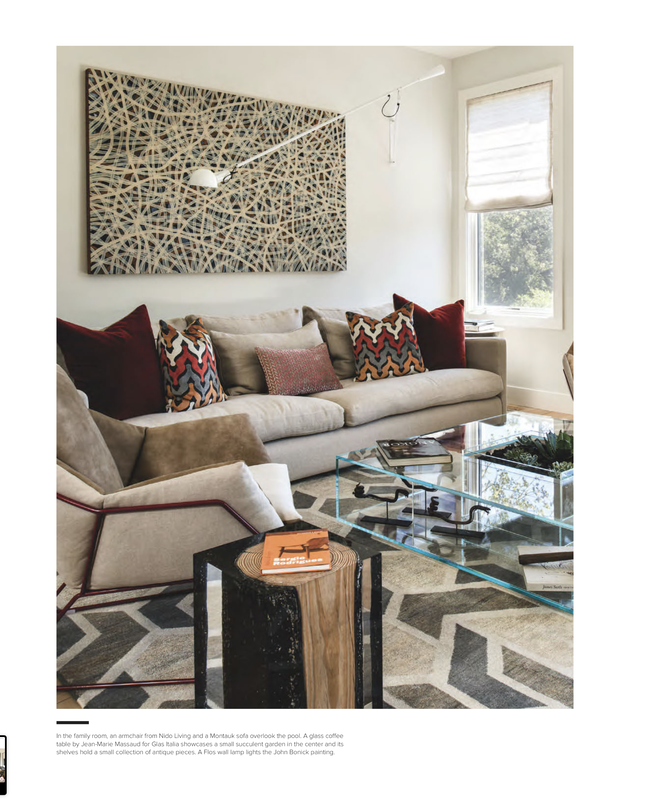

Today we'd like to introduce you to Patrick Dintino. Every artist has a unique story. Can you briefly walk us through yours? I was born in San Francisco, CA and grew up during the transition of the Bay Area from orchards and open fields to the business parks of a booming Silicon Valley. After living in Southern California and starting a band called Naked Earth, I embraced earth consciousness, championing many environmental causes. My paintings and collage reflect the blurred boundaries of this changing landscape. The color pulsations and patterns of ephemera also express the impact on our psyche of the multitude of images and persuasive influences of popular culture. I want to translate this experience energetically. With blends of color and space, I can identify a unique and timely ideal or desire in a visceral engagement. My paintings explore the complex dance of environment and technology and our inescapable connection with the information age. Just as we are mesmerized by glowing imagery from electronic media, my work hypnotizes us with breathing colored light that distills perceptions of pleasure and impermanence. Please tell us about your art I apply oil on canvas using brushes to seamlessly blend colors sampled from everyday experiences and popular media imagery. This technique results in vivid paintings comprised of diffused color bands. These bands form a color-coded framework that allows me to develop a visual language for examining the shifting nature of human perception. In my latest show, I examine the concept of what "all inclusive" means in modern-day America. Through a series of life-size paintings, I use color spectrums and perceptual distortions to represent changing beliefs about ethnic and national identities. I create color patterns of varying lengths to reflect disparities in access to opportunity in the United States. Ultimately, by using this color code as a visual language, I explore what it means for US society to be inclusive during a time of rising separatism. Choosing a creative or artistic path comes with many financial challenges. Any advice for those struggling to focus on their artwork due to financial concerns? Have many skills to draw from. I teach abstract painting at California College of the Arts, and I have graphic design experience so I can fill in some income when I need it, and it is also helpful in presenting my artwork. Recommendation by DeWitt Cheng

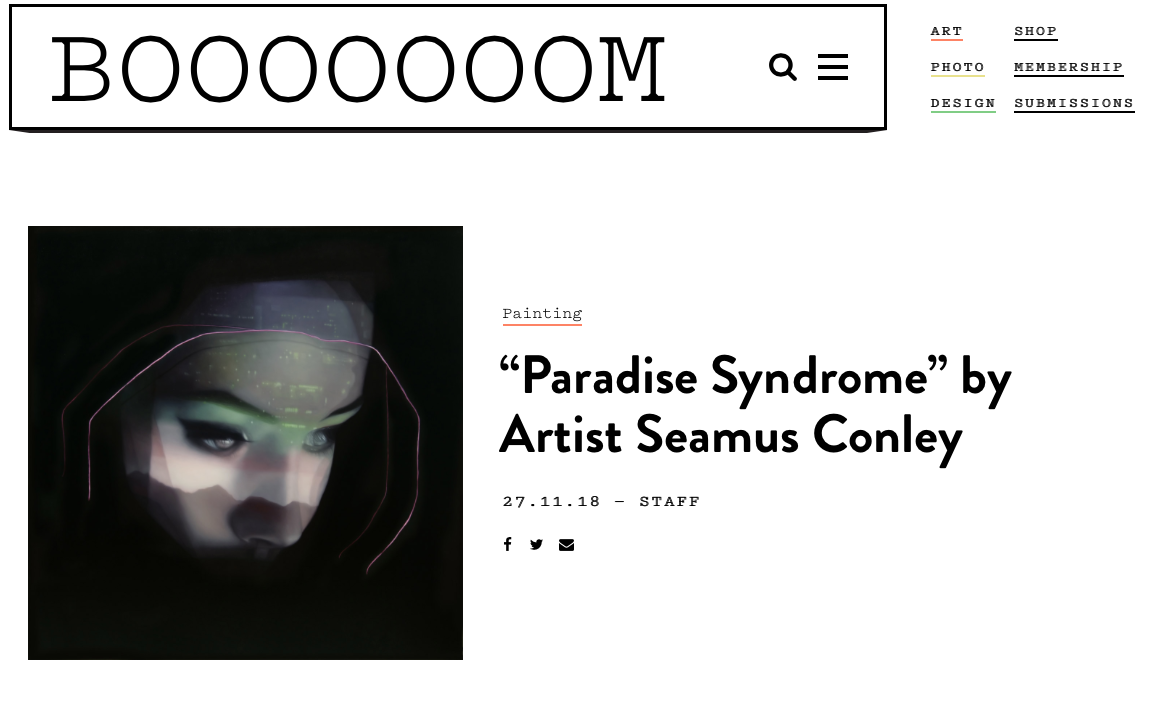

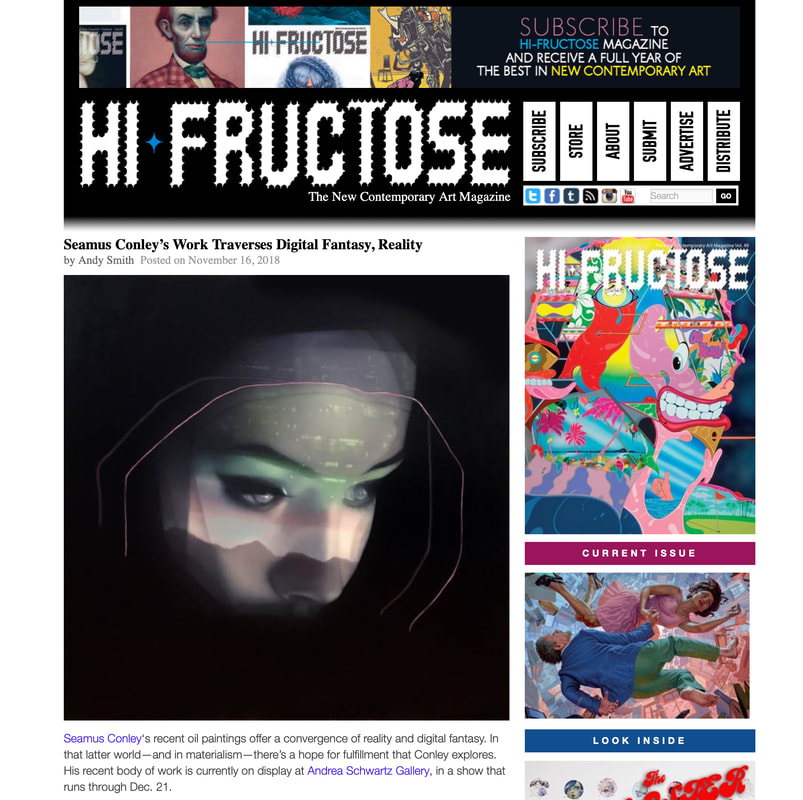

Three years ago, in "Catch My Fade", Seamus Conley showed us that realist paintings of silent, meditative figures, alone in nature, could address the concerns of hectic contemporary life. His meditative protagonists effectively are stand-ins for the viewer, "daydreaming or...wrapped up in one's internal universe while simultaneously existing in the moment of the external world." In the eight oils on canvas and three graphite drawings on paper comprising "Paradise Syndrome", Conley continues to explore the dichotomy of inner and outer worlds, reflecting on our mental states in a seductive and incessant digital age where reality and virtuality increasingly merge. In "Analog Daze" and "Blissed", a young man and a young woman, dressed in contemporary style (baseball cap, earring, and tattoos for him; a sporty dragon-motif shirt-dress for her) are caught in reflection, set against purplish-gray evening skies. A young girl sitting beside a circular window (also suggestive of a stylized open eye) in "Trillian" gazes out at the darkening clouds. "Gaze Faze" presents a young man wearing a hoodie, perched atop a mountain crag, silhouetted against the panorama of cloud-topped peaks; a comparison to Caspar David Friedrich's men confronting the sublime comes to mind. Four paintings of young women's heads, heavily made up and partially illuminated by digital-screen light reflections (think of astronaut Dave Bowman's visor in "2001: A Space Odyssey" as he ventures beyond Jupiter), are all fashion-industry chic. Are the perfectly manicured models in "Morpheme", "Oblivia", "Synthia", and "Descent" real people, or, as their names suggest, androids? A trio of small pastel and graphite drawings on paper show Conley to be a virtuoso draftsman - and a keen observer of everyday life in fraught times. Written by Mary Ore for Luxe Magazine

Raised in a house with a 24-hour wedding chapel as the living room, Oakland painter Donald Bradford couldn’t help but start out in performance art. “There was a pulpit and pews, and there were two bathrooms where the couple could change, and they would come out in their wedding clothes,” he recalls. While his uncle led the service, he and his cousins peeked out from the kitchen door, giggling at the height of the drama–the kiss. Fast forward past the third-grade teacher who noticed his artistic talent, past the bully he distracted with quick sketches of Mickey Mouse, past the two years in college studying theater arts, to the moment he realized acting made him too nervous. Bradford turned to painting, although his early canvases have a performative feel: He staged his friends in scenes from mythology and the Bible, and then he painted them. Bradford has long moved on from theatrical scenes, but his interest in narrative–and ritual–remains. He tends to do more than a dozen paintings on a theme, and his series have included 1940s love letters between a Petaluma suitor and a Wellesley College student; open books about artists; his own bulletin boards on which, Bradford says, “images and news clippings were chosen to almost set up a narrative.” In all of these works, story is suggested, but not unfolded, for the viewer. While there’s reverence, there’s also wit, as in one series in which he isolates the ritual objects of a wedding and examines each one. These are still lifes with a modernist attitude. “The classical, typical still life is a whole bunch of stuff,” Bradford says. “But I have austere, flat backgrounds, and I like doing a really simple thing– one glass with a flower in it, one open book, one votive candle.” The Bay Area Figurative Movement was inevitably an influence. “I’m probably more of a ‘painterly painter’ because of them,” says Bradford. “From far away, my work can appear photographic, but up close, the brushstrokes are very loose.” His palette, inspired by Italian painter Giorgio Morandi, is primarily “beautiful shades of white and grays with accents of color,” Bradford says. “You’d never call me a bright colorist.” The artist’s studio is three rooms off the house he shared with his late partner, Richard Bassett, a textile and Braille artist. They each had a studio and shared a “dirty studio” in between. Since Bassett’s death five years ago, “I just spread out,” says Bradford. “I go back and forth between paintings–undercoats or drawings on one, which I can make in a distracted mood, or filling out details on another, which requires real concentration.” Throughout the studio, a new series is in progress. When friends traveling in Europe sent the artist photos of hand-written prayers parishioners left in churches, Bradford soon began to write his own–for a beloved cousin with cancer, for ill friends or for those affected by mass shootings. His Prayer Paintings will appear in a solo show at the Andrea Schwartz Gallery in San Francisco from June 13 to July 20. Here, both ritual and story come together, but in these paintings, the words, too, are his own. Photos by Brandon Sullivan See full article here Written by Leah Garchik for SF Chronicle:

Five years ago, East Bay artist Donald Bradford was driving his truck across the Bay Bridge, delivering a bunch of his paintings to be shown in an exhibition at the Andrea Schwartz Gallery in San Francisco, when a strong wind blew four of them into the bay. The paintings focused on love, marriage and Proposition 8. Bradford’s latest show, “Prayer Paintings,” opened at the same gallery on Wednesday, June 13. Two weeks ago, he received an email from Carey Bell, a stranger living in Kansas. Several months after the painting, “Wedding Gown,” had gone for a swim, Carey found it floating near the shore of Alameda. He’d been working as a subcontractor for a Navy project at the Alameda Naval Base, wrote Carey, inspecting an area on the north side of the base to make sure that radiation had not escaped a controlled zone. The shoreline there “was fortified by rocks,” he emailed, and it was low tide when he saw “a painting that was resting on the rocks but being rocked by the waves. ... It was cluttered with seaweed and sand along the frame. I pulled it out and set it in the sun to dry.” He tried to locate Bradford at the time but was unsuccessful. So he took the work off the stretcher bars, rolled it up and stored it in a locker in Kansas. Five years went by, and then Bell made another stab at finding the painter. This time he was successful. “It seems amazing,” emails Bradford, “that this has happened just as my new work is about to be transported for my next show at the gallery. This time in a rented enclosed van.” |

Archives

October 2022

|

Andrea Schwartz Gallery545 4th Street, San Francisco, CA 94107 | 415.495.2090 | [email protected]

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed